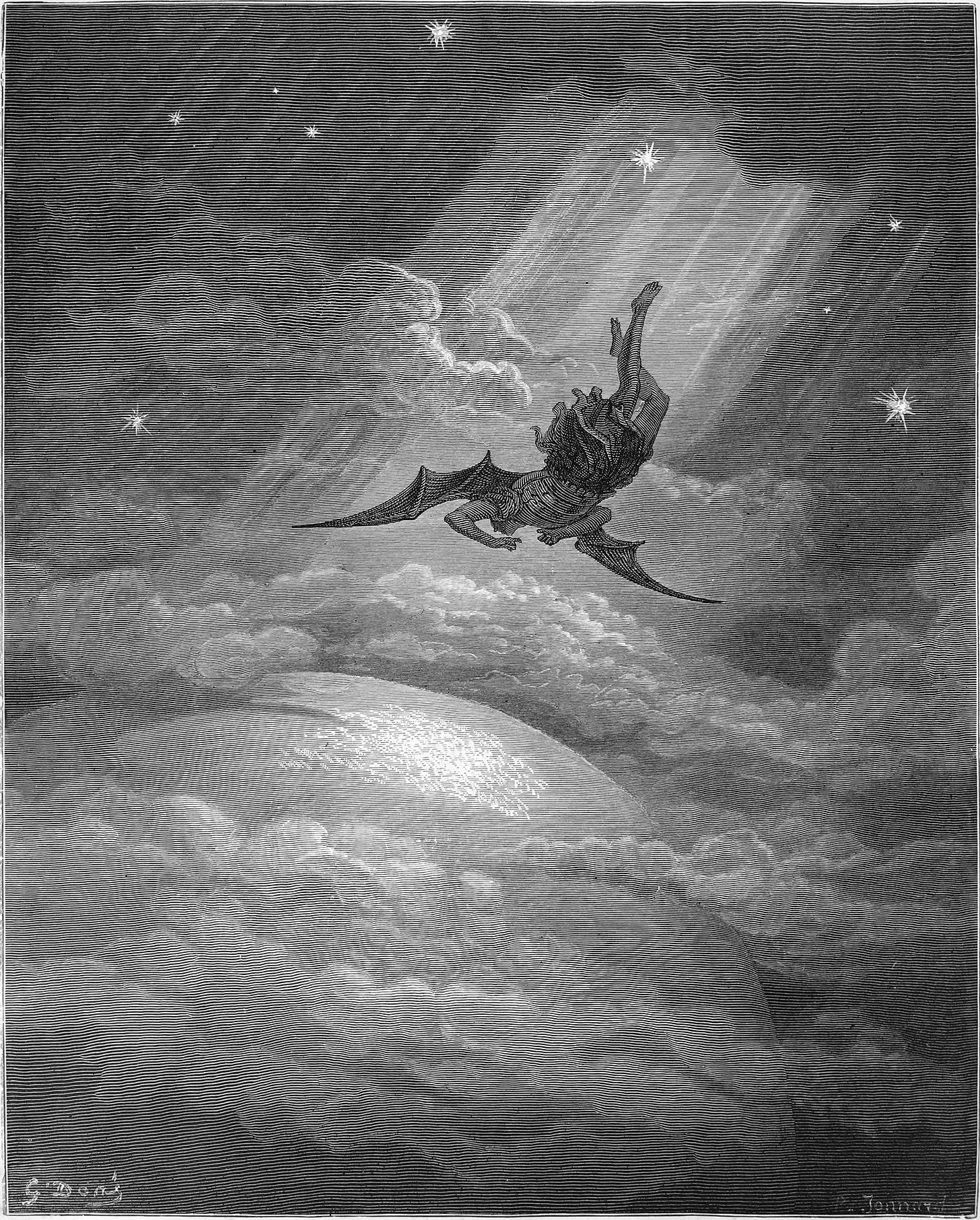

Melkor, main antagonist of The Silmarillion and looming shadow over the entire legendarium, is introduced to us on the very first chapter:

But now Ilúvatar sat and hearkened, and for a great while it seemed good to him, for in the music there were no flaws. But as the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Melkor to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of Ilúvatar; for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself. To Melkor among the Ainur had been given the greatest gifts of power and knowledge, and he had a share in all the gifts of his brethren. He had gone often alone into the void places seeking the Imperishable Flame; for desire grew hot within him to bring into Being things of his own, and it seemed to him that Ilúvatar took no thought for the Void, and he was impatient of its emptiness. Yet he found not the Fire, for it is with Ilúvatar. But being alone he had begun to conceive thoughts of his own unlike those of his brethren.

There is a lot to unpack here. To begin, the first and the second halves of the paragraph are reversed in chronological order — Tolkien introduces the antagonistic force to the Song, then does a flashback, so to speak. So let us look at the four last sentences first:

To Melkor among the Ainur had been given the greatest gifts of power and knowledge, and he had a share in all the gifts of his brethren.

Power and knowledge, in the context of this chapter, mean the share of Ilúvatar’s mind each Ainu was given. Therefore, earlier in the chapter, back when the Ainur were still singing alone, Melkor should have been able to create the best music among his peers — but no mention is made of that. Maybe the text simply fails to notice it; a more compelling explanation, however, is that, while the others were singing, alone or in groups, Melkor was already out in the Void, searching for the Flame Imperishable.

If so, this is our first sign of how greatness can become misguided. Melkor “had a share in all the gifts of his brethren”; so he knew (or should’ve known) better than any other how the different parts of Ilúvatar’s mind connected from the start. Manwë and the others, in contrast, had to take the long rout: they learned by singing, and listening to others sing. In the long run, however, this would give them way better knowledge of the mind of the Eru.

Melkor is like a naturally-talented musician who grew bored by his piano lessons. Screw notes and scores, I want to make Art! This means, of course, that he shall never play beyond what talents he already has, while his less gifted siblings, sitting diligently beside the teacher, will soon surpass him.

He had gone often alone into the void places seeking the Imperishable Flame; for desire grew hot within him to bring into Being things of his own, and it seemed to him that Ilúvatar took no thought for the Void, and he was impatient of its emptiness.

On a mere stylistic analysis, it is interesting that Tolkien once again presents the facts in reverse order: 1) Melkor was impatient of the emptiness of the Void; 2) Melkor felt the desire to bring into Being things of his own; 3) Melkor went alone to seek the Imperishable Flame.

Though not open rebellion, this is the first act of Melkor in spite of Ilúvatar’s plans. It shows that, at its source, Melkor’s fall was motivated by subcreation. He desires to create, for he himself was created. And why, oh why would Eru make him with this desire, and surround him with a Void, if not for him to fill the emptiness? If we imagine Melkor’s mind, we might picture him thinking: “perhaps this the real plan Ilúvatar has for me. Perhaps He wants me to fill the Void”. Or, if we are less charitable: “Ilúvatar is an old fool, wasting all this space where we could be creating things.”

The important point, I repeat, is that Melkor rebelion is a subcreative one; and the desire for subcreation is good, though it can be misused.

Yet he found not the Fire, for it is with Ilúvatar. But being alone he had begun to conceive thoughts of his own unlike those of his brethren.

An ominous sentence, that seems to imply that, though going into the Void was misguided, it is on his time there that the first real thoughts of rebellion start brewing in Melkor’s mind. However, notice a parallel. Melkor begins to conceive “thoughts of his own” — much like Ilúvatar had told the Ainur to adorn the Music with their “own thoughts and devices”.

What differs these two?

If we look to the beggining of the paragraph:

But as the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Melkor to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of Ilúvatar; for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself.

Melkor’s thoughts are unlike those of his brethen, because in these he calls to himself a part greater than what was assigned to him. He makes, but not by the Law. Melkor makes only by, and for, his own desires.

What Melkor ultimately wants (at this point in the tale) is to be original. To be himself that source of which “no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me”. But that is impossible. And so the only two options available to him are to follow Eru’s theme, or distort and mock it.

He chose the latter. And that is why the song he and his followers end up playing is “loud, and vain, and endlessly repeated; and it had little harmony”.

Some readers may ask if bad musical taste is such an evil act as to be called a Fall. While I do not think the text compels us to say that Melkor was irremediable straight after the Ainulindalë, I do think this passage sets up an worldview that, taken to its conclusion, leads irremediably to the evil acts of later.

Let me explain. A man in the real world who has distaste and mockery for beauty is not, of course, bound to be a murderer or a traitor. He may well be honest and courageous. But this man lives in a world which (though corrupt) is mostly good; in a body that (though corrupt) is mostly good; living in a community of people that are like him. A share of goodness is given to him by default by the very fact of being alive.

Melkor, on the other hand, lived in no world and had no body. He was purely a spirit. Iluvatár and the Ainur — and the Song itself — were all there were. And even then Melkor turned his back to them. When the Song was the only work to be done, Melkor still chose to distort it. We need not speculate if Melkor would choose himself above everything else; for when the Song was everything else, he chose himself.

The spirit of Melkor often appears in human artists (though again, and obviously, and thankfully, they are not nearly as evil as him): those who seek originality for originality’s sake, who’d rather make a mockery of beauty than curtsey to it. Luckily, there is a cure for such people: fairy-tales.

We do not, or need not, despair of drawing because all lines must be either curved or straight, nor of painting because there are only three “primary” colours. We may indeed be older now, in so far as we are heirs in enjoyment or in practice of many generations of ancestors in the arts. In this inheritance of wealth there may be a danger of boredom or of anxiety to be original, and that may lead to a distaste for fine drawing, delicate pattern, and “pretty” colours, or else to mere manipulation and over-elaboration of old material, clever and heartless. But the true road of escape from such weariness is not to be found in the wilfully awkward, clumsy, or misshapen, not in making all things dark or unremittingly violent; nor in the mixing of colours on through subtlety to drabness, and the fantastical complication of shapes to the point of silliness and on towards delirium. Before we reach such states we need recovery. We should look at green again, and be startled anew (but not blinded) by blue and yellow and red. We should meet the centaur and the dragon, and then perhaps suddenly behold, like the ancient shepherds, sheep, and dogs, and horses— and wolves. This recovery fairy-stories help us to make. In that sense only a taste for them may make us, or keep us, childish.

“On Fairy-Stories”, J. R. R. Tolkien